April 12, 2014

Population trends in periodontal diseases and implications for services in the UK – Professor Jimmy Steele

- Although oral health is clearly improving, severe periodontal disease (pocket depths more than 6 mm) is getting worse.

- Even when periodontal risk is low, the cumulative lifetime damage will have an impact. Reducing moderate disease in the population will have a huge impact.

- Dentists are currently paid on a contract initiated in 2006 but there are little incentives to support patients and treat periodontal disease. The contract reforms are aiming to deliver care according to a pathway based on managing risk with care supported by capitation. There is currently lack of clarity on treating severe disease as secondary care and specialist pathways have not been defined yet. There also needs to be clarity on where the ‘semi-specialist’ workforce will fit in.

- Overall trends are encouraging (oral health and hygiene has improved and moderate periodontal disease has decreased) but also depressing (severe disease has increased).

- Care pathways need to be validated and based on outcomes.

What we know about periodontal diseases after 3 decades of genetics research: Professor Nalin Thakker

- The pathogensis of periodontal disease is influenced by genetic as well as environmental factors.

- Inherited genetic diseases/predisposition – chromosomal (down syndrome), single gene (Gorlin Syndrome, Amelogensis Imperfecta, Papillon Lefevre Syndrome), complex (cardiovascular, diabetes, chronic periodontitis).

- Single gene defects – pathological mutations, present only in affected carriers, significantly alter the gene and protein. Single gene defects are generally due to malfunction of the neutrophil e.g. Papillon Lefevre Syndrome.

- Periodontal Complex diseases– normal variants, present in everyone, subtly alter the gene and protein. Balance is key here – more variance in DNA that predisposes an individual to a particular condition in the correct environment will have a higher tendency to develop a disease.

- Predictive power of genetic information – single gene disorder more power than multifactorial disorders. With multifactorial conditions, the individual mutations have a small effect.

- Very difficult to carry out genetic association studies – would need 50,000 to 100,000 thousand participants!

- The way we are today is a reflection of the evolution. Are our teeth lasting longer than we have been designed to live? Are dentists there to bridge the gap between evolutionary and modern lifespan? Chronic periodontal disease is not necessarily a healthy state but it may be a natural state?

Periodontal infections – Emerging concepts based on studies of the oral microbiome – Professional Gary Armitage

- Our bodies are 10% human and 90% bacteria. The microbiome is now considered an essential and dynamic oral system.

- Periodontal disease due to disrupted host-parasite homeostasis.

- Microbial carriage varies between subjects down to the species and strain levels whilst the metabolic pathways remain stable within a healthy population (Huttenhower 2012).

- Epigenetics – environment in which we live important and inflammation can change genetic composition and transmissibility.

- Periodontal disease occurs in a susceptible host who harbours potentially pathogenic microbial species. Disruption of the homeostasis occurs e.g. when plaque is allowed to build up on the teeth. Disruption of metabolic pathways causes dysbiosis and disease (Metchnikoff).

- Understanding the interactions between the human host and its bacterial community at a functional level is the most important factor (Wade).

- Keystone pathogen concept – there may be 12 or more keystone pathogens – complex. Individual taxonomic units are not as important as the overall genomic mix in the entire community. Total biomass is more important and this is generally how we treat.

- For 1 in 20 patients, microbiological testing may help but this is not strongly recommended. Only really used when this would change our treatment.

Clinical relevance of periodontal inflammation – Professor Steven Offenbacher

- Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory condition that is associated with dysbiosis of the microbiome.

- DNA methylation associated with chronic inflammation, cancer etc. Bacteria induce alterations in DNA methylation. Changes in methylation patterns of host tissues can vary site-to-site within individuals altering the hot metabolism and inflammation at a site level.

- Relationships of periodontal disease with systemic conditions linked to genetic, epigenetic and dysbiotic characteristics. The association between periodontitis and obesity may be linked to the expression of miRNAs that target genes linked to immunity and inflammation, collagen metabolism, cell cycle regulation as well as insulin and cholesterol metabolism.

- Epigenetic regulation appears to potentially explain some of the influence of environment, exposures and known risk factors on disease expression.

- The data suggests that the composition of the biofilm may, in part, be controlled by genes that modify the immune response. There are suggested susceptibility loci involved with the immune response.

The future of periodontal diagnostics – Professor Philip Preshaw

- Concept of susceptibility – specific bacteria are necessary but not sufficient to cause disease. Inititated by bacteria but host reponse to biofilm that destroys the periodontium.

- Purpose of homeostatic response important in neutralisation but if it persists or is excessive, it can lead to tissue damage.

- Probing – no information on current inflammatory state, not sensitive to small changes, somewhat subjective, limited predictive capability, time consuming, technically challenging.

- BOP – absence is a good sign of stability.

- Radiographs – looking back at the past to assess bone levels.

- What else could we measure? Periodontal inflammation? Individual immune inflammatory response – which cytokines and how?

- GCF – inflammatory mediators reflect those present in tissue but technique sensitive, provides information only about sites measuring, measurement errors.

- May use DNA probes, BANA test or genetic tests.

- Saliva – provides whole mouth information, easy to collect, acceptable to patients, useful because contains GCF.

- Specific salivary mediators are potentially indicative of periodontal status and response to treatment. Possible inflammatory markers – IL1, IL8, MMP8, MMP9.

- Benefits of developing a device detecting the above – diagnostic/prognostic information, patient self monitoring at home, testing for periodontitis in a non-dental setting – but it must give added value!

- Leading to ‘personalised dentistry’. Perhaps for specific groups of patients. Combinations of biomarkers would be more useful than a single marker and may consider using different markers in specific scenrios.

The management of smokers in periodontal care – Dr Christoph Ramseier

- Smokers have a poorer compliance to maintenance.

- Listen to your patients! May want to implement smoking cessation over multiple sessions.

- First develop rapport, then provide information and motivation followed by action. Reflect at each stage.

- Patient driven questions: ‘May I share this information with you?’ ‘What do you think about this?’ This will allow the exchange of information to be more robust.

- If the patient does not want to quit say: ‘I understand that you don’t want to quit ‘ and thereafter keep discussing the subject. Rolling resistance.

- If the patient wants to quit then offer behavioural support, pharmacotherapy and followup visits or referral.

- Focus on advantages to change and the disadvantages of not changing.

- Show empathy at each stage.

- Don’t have time? Think about where the money is coming from – patient is coming to see you and it’s worth investing in good rapport and good connection as this is the basis of your practice.

- E cigarettes – officially we do not know what to say to our patients yet!

Do we still need knives to treat periodontitis? – Professor Peter Eickholz

- When? After non-surgical therapy and anti-infective therapy has been accomplished, if effective oral hygiene advice has been provided and in case of persisting pockets more than 5 mm.

- How do you get rid of periodontal pockets – surgery: access flap, resective or regenerative.

- Access flap – questionable indications, pocket reduction works with this but if interested in attachment gain then repeated non-surgical therapy more advantageous (Konig 2008).

- Resective – apically reposition flap, tunnel preparation, root resection, hemisection etc. Resection is a good way to reduce pocket depths. With time the difference between non-surgical and Widman flap changes. With resective you sacrifice attachment gain for pocket reduction. Periodontally compromised furcation involved molars are as good as implants if treated properly (Fugazzoto 2001).

- Regeneration – furcation class II, buccal and lingual lower, buccal of uppers. Does not work in class III furcations or suprabony defects.

- Still indications for periodontal surgery as long as periodontitis is not diagnosed and treated early enough and deep infrabony as well furcation defects occur.

Implants in periodontitis patients – Dr Andreas Stavropoulos

- Limitations in current evidence and open issues. Most studies do not correct for smoking, no clear information of periodontal status before implant placement and radiographs have not usually been combined with clinical data.

- Periodontal patients do not lose more implants but have a higher risk for peri-implantitis.

- Periodontal disease needs to be under control before implant treatment.

- Supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) programme minimises risk but does not eliminate it.

- Periodontal patients may need further therapy depending on their adherence to the SPT programme.

Systemic antimicrobials in periodontics: are they useful? – Professor David Herrera

- Periodontal diseases are infections caused by specific bacteria organised in biofilms.

- SRP is effective in arresting disease progression and this may be enough for most chronic periodontitis. There is an impact on subgingival biofilms but of limited duration and only for certain pathogens.

- As part of limitations associated with mechanical therapy – patient factors and microbiology.

- Microbiology – non-specific treatment but specific bacterial species are associated with periodontitis and with disease recurrence after therapy, difficulties in elimination of certain pathogens, difficulties affecting pathogens in certain niches. Antimicrobials may help to overcome these issues.

- Role in periodontitis does exist but no clear protocol. Should be used an adjunctive to subgingival debridement (Herrera 2002). These should be prescribed after the last session of debridement and the debridement appoints should be completed within a month.

- Which patients? Studies show all will benefit but wise to select those who will benefit the most, which may include: aggressive, active, refractive periodontitis. Resistance has ben created by us prescribing to all with no need.

Risk vs benefit – should antibiotics be used as part of periodontal therapy – Professor Gary Armitage

- Use of systemically administered adjunctive antibiotics result in statistically significant clinical improvements in surrogate outcome of periodontal therapy.

- Widely acknowledged risks associated with the use of antibiotics include: development of hypersensitivity (allergy) to the drug and increasing the reservoir of drug-resistant bacteria in the world’s ecosystems.

- A newly acknowledged risk is the unintentional alteration of, or damage to, a patient’s microbiome.

- A growing body of evidence suggests that antibiotic-induced changes in the human microbiome increase the risk of developing a number of important health problems such as asthma, autoimmune diseases, obesity, diabetes, chrnic disorder of the gut, cardiovascular disease, coeliac disease and accelerated aging.

- Considering the magnitude of periodontal benefits of using these drugs as adjuncts versus the health risks to society and the world’s ecosystems, they should only be used as a last resort. Should future studies using antibiotics monitor microbiome changes?

Periodontal medicine – current concepts – Professor Steven Offenbacher

- Oral-systemic pathway: periodontitis pathway represents a systemic infectious and inflammatory burden with effects on overall health.

- Periodontitis induces bacteraemia, cytokinemia (such as increased IL-6) and hepatic acute phase response (e.g. increased serum CRP).

- Systemic inflammation, in turn, increases risk of cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, renal disease and pregnancy complications.

- Periodontal infection/inflammation is but one factor that contributes to increases in atherosclerosis, CHD events, pregnancy complications and renal impairment in humans.

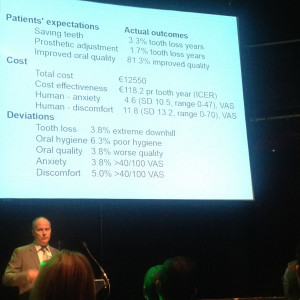

Is it possible to apply quality control to periodontal therapy? – Dr Oystein Fardal

- Quality assurance rather than quality control.

- Patient are compliant as they benefit from the reassurance and want to keep their teeth as long as possible.

- Patients also wanted their mouths to feel better – mouth feels cleaner, easier to clean mouth, less bleeding, less infection, less discomfort, teeth firmer, less sensitivity, less halitosis – seeing periodontal disease treatment outcomes from the patient’s perspective.

- There are endless periodontal variables and periodontal disease is a non-linear chaotic dyanic process so difficult to apply quality assurance

Teeth for life. Is supportive periodontal treatment needed? – Professory Gerry Linden

- Periodontal treatment without maintenance is of questionable value in terms of maintaining periodontal health.

- Cost effectiveness of periodontal maintenance needs to be considered.

- Implications of periodontal treatment with no or erratic maintenance – replaces only 2 teeth with implants before a tooth replacement strategy becomes more costly.

- Are we designed to live longer than our teeth?

Implant retained prostheses – a good choice from a quality of life prespective? – Dr Finbarr Allen

- Challenges aesthetics and patient expectations. People feel strongly about tooth loss.

- Influence of the location of the missing teeth is important not just the fact that patients have 21 or more teeth.

- Alveolar bone loss – significant consequence of tooth loss – keeping a handful of natural teeth can offer a huge advantage.

- Do dental implants help? Limited studies in partially edentate. More information for edentate patients but there are a varieties of procedures. Strong benefit of 2 implant ball retained dentures over conventional dentures for the mandible (Emami 2009).

- Initial high cost of dental implants – anatomical/quality of life/health gain. Are they worth the money?

- Implants are predictable and safe but still expensive. Also problem of completing complex surgery in the elderly.