Home/Articles

/ Periodontology /

Reena’s Notes: 18 Essential Points on the Successful Management of Unresponsive Periodontitis in Practice with Professor Ian Needleman

February 15, 2015

- A good outcome in periodontal therapy is important as successful periodontal treatment ensures the best chances of stability/retention of teeth and there is also evidence to suggest periodontal well-being contributes to an overall improved quality of life.

- Knowing the expected outcome of successful periodontal therapy is required to allow us to plan the steps needed to achieve it.

- Periodontal probing is key to measuring outcomes and it is difficult to objectively establish a good outcome by any other means.

- Why is pocket depth measurement important? There is an increased risk of tooth loss as pocket depth increases. A study by Matuliene (2008) followed a large group of patients over 11 years and found an 8-fold increase in risk of losing a tooth with a pocket of 5 mm, 11-fold increase in risk with a pocket of 6 mm and a 64-fold increase in risk for a pocket > 6 mm.

- Predictors of periodontal stability include: shallow pockets (≤ 4 mm), low levels of bleeding on probing (≤ 10%), minimal visible inflammation, low plaque levels (≤ 15%), non-smoking and no diabetes. These are important as they ensure the best chance of keeping teeth (Axelsson & Lindhe 1981, Lang et al 1990, Renvert et al 2002, Matuliene 2008). Without them, stability is less predicable and it may be difficult to ensure that patients’ expectations are met.

- The best predictor of keeping teeth is periodontal health. The described endpoints can also be used as patient information to help them understand progression and encourage ownership of their periodontal condition.

- Diagnose the key factors leading to a lack of response. These can be divided into:

(i) Local factors – deep pockets, infrabony defects, furcations/root grooves.

(ii) Patient factors – health behaviours (oral hygiene, compliance to appointments), is it possible to clean, restorations margins/embrasures, tobacco use, diabetes. Often these factors tend to cluster together.

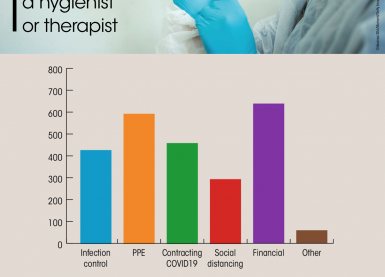

(iii) Professional factors – instruments appropriate for root debridement (curettes/ultrasonic tips, sharp/properly tuned), skill (tendency to de-skill) and behaviour change (difficult skills). Working as a team (with hygiene/therapists and other health professionals) to implement care-pathways and joined up treatment planning can be helpful. - Key causes of lack of response are usually well characterised and many can be identified at initial assessment. By identifying limitations early helps forecasting and appropriate forecasting promotes motivation and adherence to successful treatment.

- Plaque control – for control of periodontitis, patients need to achieve and maintain great plaque control. Information alone is not motivation. How to influence patient oral hygiene behaviour effectively (Clarkson et al 2009) – Tell (clean teeth feel smooth to the tongue), show (show how tight interdental brushes should feel), do (ask if now confident), plan (elicit an action plan). New resources for periodontal health: SDCEP video, delivery better oral health toolkit.

- How effective is non-surgical periodontal therapy? Hujoel (2000) performed a practice-based study with 1000 patients. Continuous non-surgical therapy over 3 years resulted in a 60% reduction tooth loss and intermittent non-surgical therapy resulted in a 48% reduction in tooth loss. Cobb (1996) found non-surgical therapy reduces pocket depths by 1 mm in moderate pockets (4-6 mm) and a reduction of 2 mm is found in deep pockets (7 mm or more).

- When making the decision of whether or not to repeat non-surgical debridement, it is important to first understand how effective it is and if the expected results are likely to achieve a good outcome. One must consider the limiting factors, such as infrabony defects and furcations. Clarify what you and your patients are expecting to achieve from the repeat treatment.

- Root surface debridement – Aim for thorough removal of all dental plaque and calculus but remember that the bacteria and endotoxin are located superficially on the root surface and calculus. Cover the entire exposed root surface with overlapping/cross-hatching instrument strokes. Remember that ultrasonic instruments only work at the point of direct contact between the tip and root surface. Practice and assess your technique using stained teeth (instruments/strokes/angles/time), extracted teeth and noting where there is residual calculus following surgical access. There are a variety of tip designs for hand instrument but they do need to be kept sharp. Ultrasonic instrumentation is possibly less technique sensitive but the tip design is more limited.

- Systemic/local antimicrobials – Some systematic reviews suggest systemic antibiotics can produce small improvements as adjuncts to treating severe or active chronic periodontitis (Herrera, Needleman, Sanz & Moles 2002; Haffajee & Socransky 2003). The decision to use antibiotics needs to be balanced with their effectiveness and safety such as bacterial resistance. If using antimicrobials, it is important to perform thorough debridement first. If you are considering the use of antimicrobials, this probably indicates a patient for referral.

- Smoking – Less probing depth reduction following non-surgical/surgical therapy (Needleman et al 2007; Labriola, Needleman & Moles 2005, Ah et al 1994); Greater disease recurrence or continued attachment/bone loss during maintenance (Machtei et al 1998, Meinberg et al 2001). Cutting down has little benefit as individuals who cut down tend to smoke more heavily on fewer cigarettes (Jarvis et al 1997). However, clinical improvements are greater for quitters compared to current smokers within 12 months (Rosa 2011). The use of the NHS stop-smoking services (nhs.uk/smokefree) almost triples a smoker’s odds of successfully quitting compared with going alone or relying on over-the-counter products (R West). Offer referral if severe disease of unresponsive.

- Diabetes – Poor/unstable glycaemic control reduces the benefits of periodontal therapy. It is a good idea to contact the physician to find out about the stability, as this will encourage closer diabetes care. HbA1C indicates control over the previous 4 months. There is a move to describing the HbA1C level in mmol/mol rather than percentages. Good control is <48 mmol/mol (<6.5%). Be a supporter as plaque-control is yet another element of self-care for these individuals. Offer referral if severe disease of unresponsive.

- Periodontal surgery – Used less often than in the past. Usually for localised areas in challenging cases. For deep pockets (> 6 mm), surgery achieves greater reduction in probing depths and gain in attachment 12 months after treatment. But there is no evidence of a difference after 12 months, but limited data (Heitz-Mayfield et al 2002). Serino et al (2001): Surgical therapy was more effective than non-surgical scaling in reducing the overall mean probing depths, eliminating deep pockets and reducing chances of progression. Therefore surgery achieves greater pocket depth reductions and attachment gains for initially deep pockets and greater pocket depth reduction is associated with less frequent recurrence of periodontitis. The limitations of non-surgical therapy e.g. infrabony defects can be recognised at the outset and predictions of likely need for surgery can be made. Overall, the key issues are the critical importance of effective daily plaque removal as well as the need for effective root surface debridement.

- If the patient is unresponsive/deteriorating, offer referral – perhaps having tried 2 courses of non-surgical therapy. It may take time for patients to accept care. The BSP has produced guidance on when to refer. Complexity scores (1-3) can help guide which cases are best suited for referral.

- Periodontal treatment is usually highly successful – more successful than dental implants.

The BSP website is a fantastic resource for all – www.bsperio.org.uk

Don’t forget to register for EuroPerio8 – www.efp.org/europerio8/